After 24 days of holding out hope that some troubling symptoms were curable, followed by 22 days of watching the realities of an awful incurable brain disease take shape, my mom died Tuesday evening. My dad, my brother, and I were close by when she passed on December 20th, 2016.

The 46 days leading up to this event have been heart-wrenching. Watching someone you love suffer and wither away before your eyes is an experience I hope none of you have to face. And if you’ve done that already: my deepest condolences from a place of unfortunate understanding.

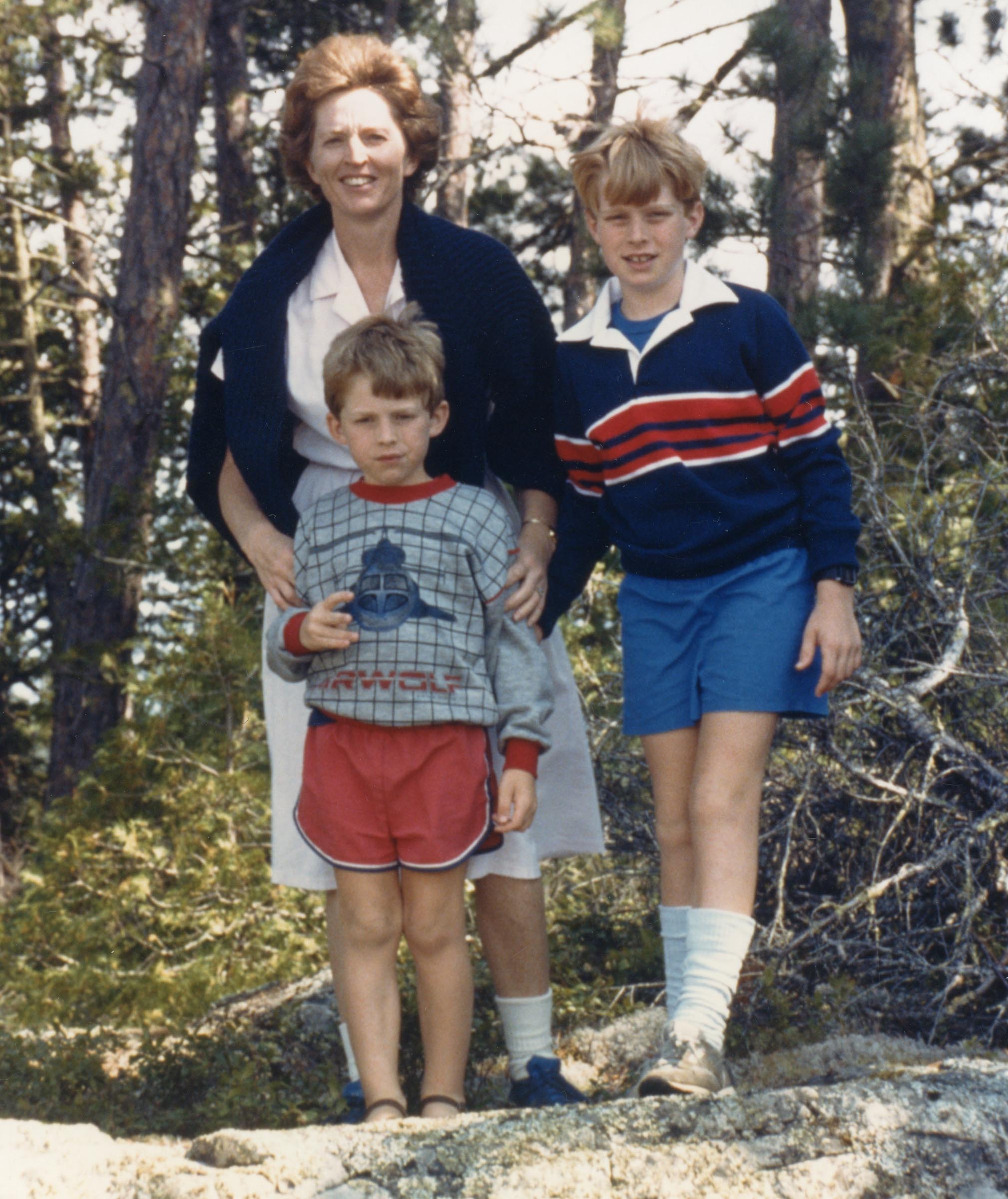

Christmas 2012

I’ve been fearing the death of my parents since I was ten or so. I was probably more tuned into it than most thanks to my Mom’s sense of morbid reality — like when she reminded us during the Christmas of 1988 that we should talk with our grandmother in Australia because she “doesn’t have much time left.” And then reminding us again in 1989, 1990, 1991, and the next fourteen Christmases until she died in 2006. You’d think that after a lifetime of thinking about death, I’d be more ready for it. But who is ever ready for this?

Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease is terrifying and unstoppable, and I’m confident that had it been anything else she may have survived. Her side of the family was a tough bunch — my grandmother survived diabetes, Alzheimer’s, and a tennis-ball sized brain tumor, living to 95 years old. My Mom survived Diphtheria and Typhoid Fever in Zambia as a child, and in the last few years breezed through two hip replacements and two lens replacements like it was nothing. And then, of course, there’s what I consider her greatest medical feat: birthing me — an eleven pound baby — and then putting up with me through my adolescence.

1981

But it took a rare one-in-a-million disease of mystery origin to defeat her at the age of 71. Nobody saw this coming, and I can’t say I was ready for it. But again, who is ready for this?

2003

Well, my mom was more ready than any of us. For years I rolled my eyes when she’d tell me she was sorting through and throwing out old stuff.

“I don’t want you to have to deal with all this after I pop my clogs”, she’d say.

A few years ago, after my parents retired and moved to Austin, they signed up for The Neptune Society. It’s a prepaid service that handles everything after someone dies — from removing the body, to cremation, to the scattering of ashes. I remember mom excitedly telling me that all we’d need to do whenever that time comes is to get some documents out of the freezer, call the number on the card, and everything will be taken care of.

At the time I thought this was ridiculous and quipped “Wow! What a timesaver! We’ll barely have to grieve!”

In the past few weeks while digging through documents, her preparations continue to amaze me. Lists of passwords and instructions of what to do “if she dies first or loses her marbles”, with a paragraph reminding my brother and I that “going through a parent’s things after a death is not easy, but remember that it’s just stuff.”

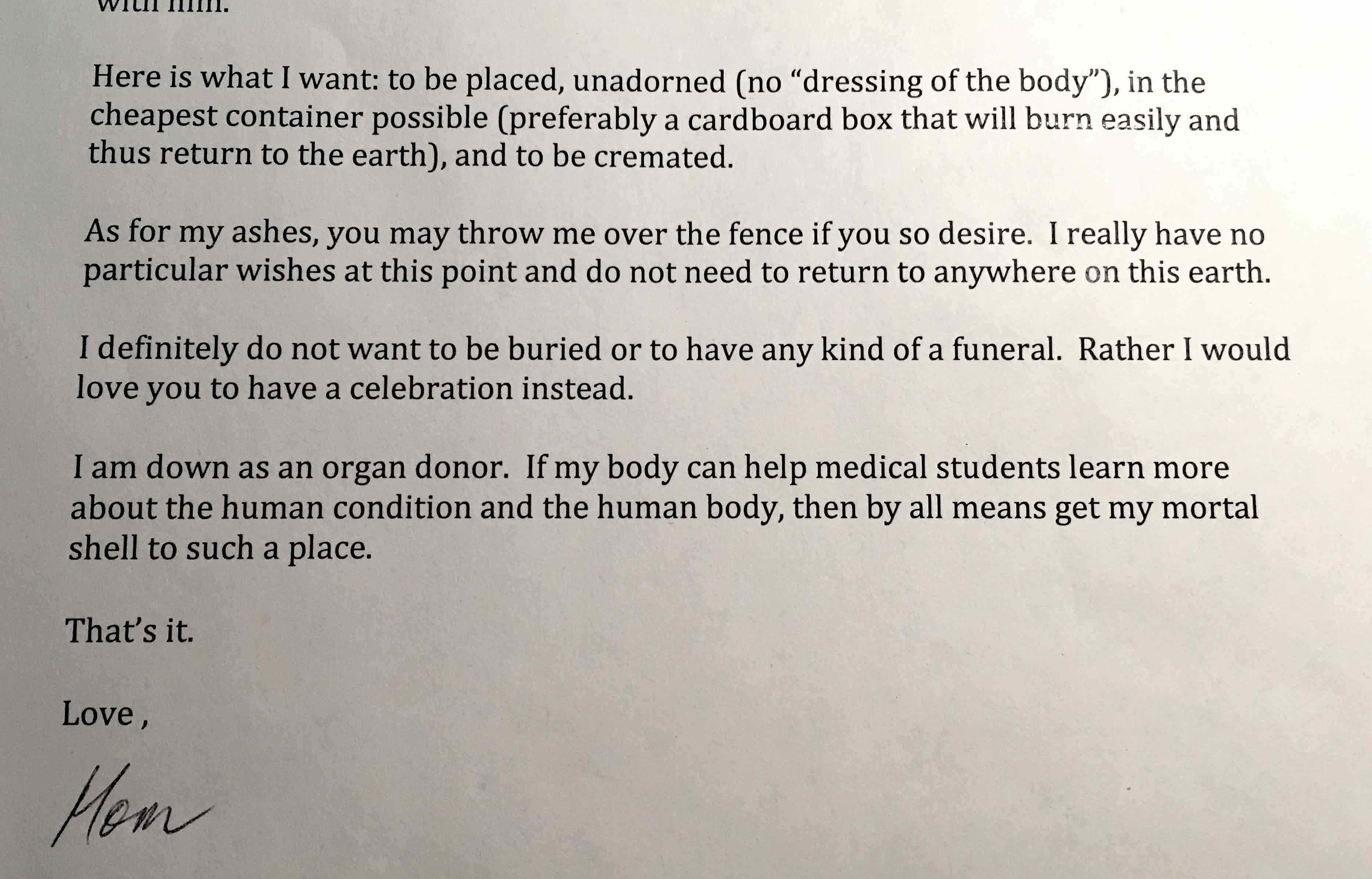

Only now do I appreciate all the time and effort she spent preparing us for this unexpected time, and that her wishes were made crystal clear.

Here is what I want: to be placed, unadorned, in the cheapest container possible (preferably a cardboard box that will burn easily and thus return to the earth), and to be cremated.

As for my ashes, you may throw me over the fence if you so desire. I really have no particular wishes at this point and do not need to return to anywhere on this earth.

I definitely do not want to be buried or have any kind of funeral. Rather I would love you to have a celebration instead.

I am down as an organ donor. If my body can help medical students learn more about the human condition and the human body, then by all means get my mortal shell to such a place.

A life-long educator, she was adamant that after her death everything be done to help others. And even on the 28th of November when we all received that heartbreaking terminal diagnosis, with her ability to communicate already crippled she determinedly told the neurologist that she wanted her experience to help people. To help in the study of prion diseases, as well as help him (a fairly new Neurologist) get his first publication out of the deal.

(We’ve arranged that her brain will be donated to the Case Western center for prion disease study, which will hopefully help the world get one step closer to finding a cure for prion diseases.)

My dad has requested to our family friends that “instead of sending flowers, cards, or sentimental writings, what would mean so much more to us/her would be to get a copy of a nice, meaningful and soul-uplifting book that has had some special meaning for you, and for you to give it to someone in memory of Colleen. Let her quest as a life-long teacher be passed along.”

I’d like to add upon that theme and request that you take something away from my experience.

In the last six weeks, my family’s dynamic has completely changed. This thing broke down walls between us made us all realize what’s important, and now we all can’t help but think “what took us so long to get here?”

My dad has been opening up and sharing stories of his life, his parents, and his experiences while my brother and I stare at him with our jaws on the floor. I always knew that my parents had lived incredibly rich and interesting lives, but I never really took the time to absorb or appreciate the details. For too many years I considered myself an anomaly in my family and thought to myself “I am who I am in spite of them”, only now realizing the obvious: I am who I am because of them. Shame on me.

I think about how my parents have lived a mere 10 miles away from me for the past five years, and yet most of the time I found it a monumental effort to make time to join them for tea. I’d often receive calls like this (voicemail) from my Mom:

I’d listen to it and think, “yeah yeah Mom, I’m busy. Some other time.”

I don’t think I need to tell you how how much time I’d set aside, or how many miles I’d drive for another cup of tea with everyone.

So I make this request to you:

Think about mortality and contemplate losing the people close to you until it makes you feel really uncomfortable, and then let that uncomfortable sense of reality diminish the feelings of frustration you have with them. Permanently cut them all more slack than you think they deserve. Ask them the questions you’ve been meaning to ask. Tell them the things you’ve been meaning to tell. And most importantly, choose to find the genuine love and appreciation you have for them before a tragic event forces you to.

“Death is an inevitable part of life and it must come to us all”, my Mom said in one of her notes, written years ago. It’s a pretty shit part of life, if you ask me, but what else can be done with life’s shit than turn it into fertilizer?

For my entire life I watched my mom always put herself last in order to benefit the people she loved. And now, at her own expense, she’s pulled us all closer together. I wish she were here to see it.